- Home

- Charles E Gannon

Marque of Caine Page 3

Marque of Caine Read online

Page 3

Once there, they would be in range to commence terminal operations.

Chapter Three

JUNE 2123

NEVIS, EARTH

As Riordan finished buttoning his shirt, his wristlink chirped: a pending text message. Prefixed with a secure code he had only seen four times since arriving on Nevis. He authorized delivery, frowned as he read:

Antigua InterIsland Holidays:

The ultimate experience!

Riordan ignored the rest of the advertising copy; it was meaningless window-dressing. Instead, he double-checked the origination code: it had not come from the off-shore agents’ secure number on St. Kitts, but rather from the remote hub on Antigua. More importantly, the code phrases were authentic.

Specifically, “Antigua InterIsland Holidays” was the online business shell in which Caine’s protectors back in DC housed a direct comm link to him. The second line—“The Ultimate Experience!”—referred to his imminent death, not a unique island tour. The protocol triggered by that phrase required Riordan to presume himself completely compromised. He could not even trust the two agents on St. Kitts.

Reacting more than thinking, Caine started down the standard action list. Item number one: alert Connor.

But Riordan stopped his index finger in mid jab. No. This was Ultimate Experience, the only condition that necessitated a reassessment of all security breach SOPs. Because if the breach was the result of an intel leak, then the enemy was almost certainly waiting for Caine to follow his assigned game plan.

Meaning that was precisely what he must not do. Alerting Connor would bring him back early, which was more likely to endanger than protect him; he was almost certainly not a target. But if the threat force expected Caine to signal him first, then—

Riordan took two long steps back into the kitchen, extracted his small go-kit from the hollowed-out heater. He opened it, pocketed the small liquimix pistol and scooped up the three micro drones. He brought up his wristlink’s emergency command screen, touched it to the first microdrone, tapped a preset code that would have it follow the road directly to the air terminal. Riordan made one change. Instead of the drone emitting Caine’s transponder code, the drone was now set to imitate Connor’s. Riordan launched it. Humming, the tiny drone sped out to the veranda and dove out of sight toward the road.

The next two drones didn’t need any modifications to their preset routines. He set the first one loose from the front door, ran down to the car with the other. He opened the driver-side door, rolled down the windows, turned on the engine, tapped the dashboard, selected “regular destinations.” He chose the long route to Charlestown—twenty-two kilometers—and stepped back as the vehicle started driving itself down the hill. Illegal, of course, but he’d be happy to answer for it later. If he was still alive.

Patting his pocket to make sure the water bottle hadn’t fallen out, Caine made for the trees at the double-quick.

* * *

As the two drones from the Golden Hold reached the twelve-o’clock position of their partial circumnavigation of Mount Nevis, their sensors registered three new transponders, all transmitting mission-critical codes.

One signal was not the target’s code. It belonged to the target’s child and was useful only as an ancillary indicator. It might be co-located with, or close to, the target itself. But in this case, the child’s signal was moving north on the main road, away from the other three. Whether it was heading for the air terminal, Charlestown, or some other destination was immaterial to locating the actual target. However, it did trigger a recalculation of the mission’s completion parameters and a drastically reduced timeframe. With the ancillary signal moving away from the target, there was a significantly increased likelihood that the child was attempting to summon reinforcements for the target. The mission had to be completed before that was accomplished.

However, the far greater challenge to the drones’ self-learning systems was to assess how and why the original target transponder had suddenly transformed into three separate but identical signals, which were now moving on entirely different trajectories. One was apparently following the main road south at vehicular speed, directly away from the projected engagement zone. It was too early to calculate possible destinations or determine if this was simply a diversion.

The second signal was moving at human speed, but heading due east, either down to the small community designated as Brick Kiln or beyond it to the rocky Atlantic coastline and the wind turbines arrayed along it. Again, the destination could not yet be projected and diversionary movement was certainly a possibility.

The third signal was making slower progress in the opposite direction, heading toward Mount Nevis on a highly irregular course. This made it an excellent candidate for being the actual target: the movement was typical of humans, not machines. On the other hand, since there were now three identical signals moving in different directions, scenario algorithms indicated near certainty that the target was aware of the impending attack. It might have had time to program an automated device to mimic human movement. Data on the tactical sophistication and inventiveness of the target multiplied the likelihood of him employing such a ruse.

Probabilities and odds were integrated and compared, assets measured. It took an inordinately long time—almost two whole seconds—for the drones to arrive at their optimal response.

As they drew within five hundred meters of the original engagement zone, the discus-sized drone activated its three subdrones, each about the size of a clay pigeon. The discus slowed, giving them a stable launch platform as they rose up. One buzzed eastward, chasing the transponder signal heading for the coast. The other two joined the larger drone, which swerved southward in pursuit of the signal wending its way through the jungle. All variables considered, it had the highest probability of being the actual target, which, along with the difficult terrain, warranted the extra assets. The discus itself swung to follow the main road southward. Chasing a vehicle while remaining in contact with the larger drone required its superior speed, endurance, and transmitter.

* * *

Riordan was gratified that he was not panting yet, even though he had pressed himself hard for the first fifteen minutes.

Still moving, he sipped from the water bottle, replaced it, and veered off his accustomed route, taking a game trail to the west. So much for this morning’s refreshing hike in the woods; now, it was a run through the jungle. He recalled a song by that name, played by one of the cryogenically suspended Vietnam War veterans that his team had found and rescued during the mission to the Hkh’Rkh colony world of Turkh’saar. The chorus of the song felt particularly appropriate, just now.

The game trail ended after fifty meters, reducing his progress to a slow, stumbling trot. The tall, thin tree trunks were thick around him, the stone-littered ground slimy with moisture and rotting leaves.

But this short cut reduced the distance by two-thirds and there were no clear sight lines. The region’s occasional hikers stayed on the trails, so they didn’t create new paths or gaps in the foliage. Whoever or whatever might be following Riordan would be hard put to follow, let alone keep up with, him.

Unless, of course, they had the codes that could dupe his surgically implanted transponder into emitting a ping: then they’d find him no matter where he went. Which made it all the more important that he reached the ravine before they reached him.

Up ahead, he could hear the distant chatter of a thin watercourse falling over rocks. He sprint-stumbled toward it.

* * *

The large drone and its two small scouts halted in front of a wall of tree trunks. The subdrones would certainly be able to weave their way forward, but it was impassable for the larger one. As a group, they reversed out of the dead end: the third one that had stymied them since the target’s transponder had moved off known trails. The large drone’s considerable self-learning program—mislabeled its “brain” by overenthusiastic academics and the journalists who believed them—analyzed the pr

oblem.

The crucial variable was the uncertainty of navigational outcome. The position of the target’s transponder was well-established; the trees did nothing to block the ping-backs. Standard algorithms had initially recommended a straight-line intercept, relying upon forward-looking radar scans to detect and follow vectors where the foliage was less dense. Unfortunately, the jungle continued to thicken and radar penetrated less than fifty meters. Each time, what started out as a comparatively clear path slowly became impassable.

At this rate, statistical analysis indicated that the target would reach the other side of the island before the drones effected intercept. And if the target’s child—whose signal was now nearing the air terminal—was seeking assistance, he would surely find and return with it long before then. That mission-failure condition would immediately trigger the drone’s self-destruct protocol, thereby minimizing forensically useful evidence.

The big drone’s self-learning analytics ran through higher-risk intercept options. Rise and maneuver to a point directly above the target, then attempt to descend through the jungle canopy? Contraindicated. Despite increasing the risk of detection by both local law enforcement and any target-friendly assets that might be in covert overwatch, the vertical assault option still did not guarantee success. Observational data was indeterminate regarding the canopy’s obstructive characteristics, but radar showed it to be unpromisingly thick. Any significant delay during descent would certainly give the target ample opportunity to detect the drone’s audio signature and possibly inflict damage while it was vulnerable.

The self-learning system went further outside its optimal mission parameters and engaged less conventional subroutines: heuristic learning, historical examples, human prediction algorithms. All analyses produced the same result: return to the trail. It was the longer route by a factor of three, but its unobstructed flight path would allow the drone to eventually overtake the target. The only drawback was increased risk of detection by other humans—the risk variable that weighed most heavily against any autonomous departures from the precoded scenarios.

But no other option promised comparable speed and efficacy, and the risk was no worse than a pop-up attempt to effect an overhead intercept.

The two subdrones reversed, sped back toward the trail that twisted through the jungle like a serpent. The large drone followed at a distance of twenty meters.

* * *

Riordan had not come this way often enough to recall the subtle differences in the trees that signified he was nearing his goal. A surge in daylight—sudden and bright—triggered a shielding reflex with his hand. It put him off balance just as he remembered that the small clearing was a half step below the jungle floor. He tumbled forward.

A faint sulfur stink hit his nostrils as his chest and cheek hit the slimy mud. Might as well get used to both. He pushed up on his arms, looked around. No sign of pursuit. The trail here was more overgrown than before: the hiking traffic had been low and the sightlines were more limited than usual. All to his advantage.

Riordan rose and looked across the small clearing, where a crevice almost bisected a wedge of volcanic rock that pushed through the foliage. It was the cavemouth he’d been heading for: a tapering spearhead of black shadow, two meters from base to tip.

Moving from rock to rock to avoid the mud, Caine quickly crossed to and entered the cave, tapping his wristlink three times for maximum illumination. As on his prior visits, the mud had pooled back into the cave itself. The morning run-off from Nevis carried dirt down the slopes and kept the ground wet.

The light from his wristlink picked out the walls’ most jagged protrusions: every inch was rough and irregular, like most of the island’s volcanic vents. He smiled.

Dimming his light, he felt for and located a short left-hand switchback tunnel that was more like a hidden alcove. He shone the light higher, saw the small natural ledge he’d found twenty months ago. Riordan reached up cautiously. It was a little close to the entrance for bats, but you could never be sure…

Fortunately, his fingertips brushed against smooth, dry plastic, not leathery wings and sharp teeth. Pulling down the bag, Riordan inspected its seal: still tight.

The contents—mostly communications gear—showed no sign of water damage. They had been left behind at the house that Richard Downing’s family used to own, just a few miles further south on the ring road. It was also where Elena’s brother Trevor had linked up with the ops team that he had led to Indonesia. Needing to travel light, they had left behind a small stash of equipment, the location of which Trevor had shared just before Caine began his voluntary exile on Nevis.

Caine had excavated the gear his first week there, but much of it had already been discovered by the implacable foe of all hidden tropical caches: water. Half of the electronics were ruined, as were the two handguns that might have proven handy. But spec ops teams carried lots more than guns and radios, and enough of the equipment had survived that Caine resolved to hide it in a safer, higher, drier place.

Just in case.

* * *

As Connor climbed down Booby Island’s stony northern flank, he heard a faint high-pitched growl cutting through the rising and falling surges of the windward surf. He scanned the sky directly over St. Kitts: nothing. But when he widened his sweep to the ocean, he detected a small dark blot far to the west, coming around the leeward bluff known as Nags Head. The blot grew larger, but did not move to the right or left.

Which meant it was heading straight for Booby Island.

Connor turned and swiftly clambered back up into the gnarled trees, the midday sweat suddenly cool on his body, the grip of the sloop’s pistol slick in his hand.

* * *

As the main drone and its two small reconnaissance platforms neared the target’s transponder, they slowed: the signal was coming from a mass of what seemed to be solid rock. One of the subdrones swung wide and flanked the volcanic spur that protruded into the clearing. Ladar scans confirmed the AI’s conjecture: there was a cave opening.

The main drone updated and assessed the summative operational situation. The discus-sized drone that had followed the signal heading south indicated that although it was slowly gaining on its target, it might not effect intercept before draining its battery.

The third subdrone was still tracking the signal that was now following Nevis’ rocky eastern coastline. There, the difficulty was not speed but unexpected terrain obstructions—obstructions that the target was courting to frustrate and extend the pursuit.

But it was precisely that similarity between those two targets—that they were attempting to evade, rather than elude—which suggested that the signals were emanating from decoys. A human would not settle for evasion or mere delay. A human’s survival instinct required nothing less than complete escape or complete concealment. Which meant that the signal in the cave was almost certainly the one emanating from the actual target.

The large drone advanced its subdrones to further assess the environment: the cave mouth was large enough to admit a human easily. Scanning the internal layout from outside was impossible without a sophisticated densitometer, a device many times the mass and volume of the drone itself. The geographic feature into which the cave penetrated was otherwise solid rock, rising up a further three meters and terminating in a wildly overgrown shelf that was itself an extrusion of the larger, higher slopes of volcanic rock. If there was any means of flying upward to achieve vertical descent into the cave, ladar scans did not reveal it.

The drone’s AI chewed at the problem, quickly reduced it to a single operational option. Send a subdrone into the cave to acquire a 3-D ladar rendering of the layout, and, in the course of doing so, attempt to close with the source of the transponder signal. The main drone would follow relatively close behind. If the target emerged to destroy the subdrone or flee, it would be eliminated. The other subdrone would maintain a rear watch and remain in reserve as a potential replacement for the first subdrone.

O

bedient to the main drone’s summons, the lead quadrotor abandoned its fruitless survey of the overgrown upslope ledge and made for the cave mouth.

Chapter Four

JUNE 2123

NEVIS, EARTH

Riordan peered closely into the cracked corner-checking mirror. Although the combo goggles from his stash were half-broken—the thermal imaging was busted—the light intensification enabled him to see a small object float into the cave. Drifting only ten centimeters above the rough floor, it edged forward, swiveling slowly.

As Riordan watched it work, he kept the mirror in close contact with the surrounding stone. The drone was evidently creating a 3-D map of the cave. Too small to be an attack element but, whether another drone or humans were in charge of the operation, that command element had wisely decided not to enter the cave blind. Yet, the little quadrotor’s sensors were a heavy load for its small fans, which suggested a comparatively short range and limited battery life. Its home platform, whether carried by a human operator or mounted on a larger drone, was probably nearby.

However, humans would have been hard pressed to arrive here so quickly. Even if they had a fix on Caine’s transponder, the trail leading to it often branched in counter-instinctual directions. Pursuers on foot would have had to guess the correct turn every time in order to be here already. But drones were fast enough that they would have been able to have guess incorrectly several times and still be on site by now. So, the proximal elements of the pursuit were likely to be purely automated.

Furthermore, the movements of the drone suggested a machine controller. Every action, no matter how small, was precise: no wobble, no lingering or reversing to inspect an unusual feature. Machine controllers never reassessed what they had already assessed, just as following a “hunch” was not within the scope of their processors.

As the little quadrotor crept further into his mirror-reflected field of vision, Caine refined his hypotheses. Autonomous strike assets were also likely when an enemy’s highest priority was anonymity. And whoever wanted to kill Caine was probably even more determined to remain unimplicated.

At the End of the World

At the End of the World Marque of Caine

Marque of Caine Fire With Fire-eARC

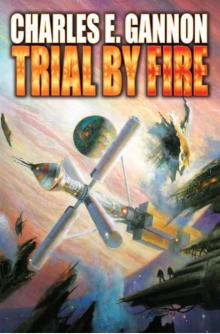

Fire With Fire-eARC Trial by Fire - eARC

Trial by Fire - eARC Fire with Fire, Second Edition

Fire with Fire, Second Edition Trial by Fire

Trial by Fire Raising Caine - eARC

Raising Caine - eARC